ROI in loyalty programmes

Authoring a blog dedicated to the international community of experts entails a careful selection of the topics to be covered. The matters discussed should be universal and therefore relevant to all, whether the reader lives in Sydney or Stockholm. At the same time, it should be general enough not to alienate those who are just starting out in loyalty management and not to discourage those who have been working in the industry for years.

Since the motto of the i360 blog is “From everyday work taken from everyday work”, I always try to describe topics that my readers would find useful in their daily work. Very often these topics are the result of conversations, whether those had during business meetings or loyalty conferences, or, as in this case, the implementation of a project for one of our customers. You will admit that the topic of ROI (return on investment) in loyalty programmes meets all the above criteria. At the same time, as a subject for which you need to “get your maths right”, it is rarely discussed in materials devoted to such programmes.

The following text is a case study of the preparation and implementation of an ROI model for one of the retail chains with more than 150 European retail outlets in the fashion and apparel segment. The model was prepared prior to the implementation of a loyalty programme dedicated for end buyers and formed the basis for determining KPIs (key performance indicators). These went on to become the main goals for all the entities and managers involved in the work on the programme.

According to the most basic definition of ROI, as provided by Wikipedia, it is a ratio between net income (over a period) and investment (costs resulting from an investment of some resources at a point in time). A high ROI means the investment’s gains compare favorably to its cost. As a performance measure, ROI is used to evaluate the efficiency of an investment or to compare the efficiencies of several different investments. In economic terms, it is one way of relating profits to capital invested.

Our task was to create a model that would enable the Management of a company implementing a loyalty programme to assess several factors. These included the time after which the expenses incurred in launching and managing the loyalty programme would pay off, as well as the rate of return on invested capital. To make this possible, we were tasked with creating a mathematical model that would allow the above to be estimated. This model had to take into account all the actual market environment variables, as well as a structure reflecting the current situation of the company.

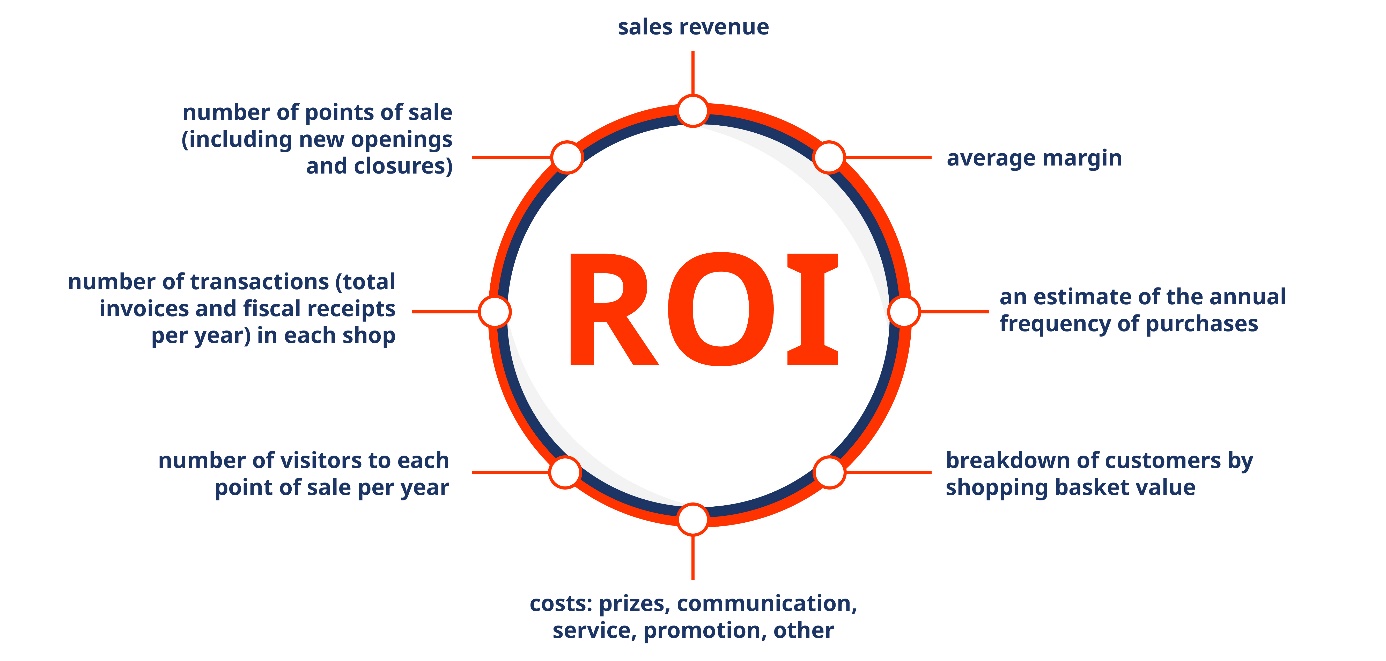

Fig. 1. Selected inputs for the retail chain ROI model

Input data

As with most retailers, obtaining information on the value of key descriptive variables was not a problem. Hence, the following were included as model inputs, among others:

a/ number of points of sale (including new openings and closures)

b/ number of transactions (total number of invoices and fiscal receipts per year) per point of sale

c/ number of visitors to each point of sale per year

d/ sales revenue

e/ average margin

f/ an estimate of the annual frequency of purchases

g/ breakdown of customers by shopping basket value

The above list represents only a fragment of the entire range of variables adopted for the analysis. However, the above seven main inputs accounted for more than 85% of all data in terms of their weighted significance in the scoring scheme adopted for the model.

Determining the above formed the foundation for the ROI model, as any model is only as good as its inputs, according to the ‘garbage in – garbage out’ principle. A key aspect of the process of laying the foundations for the ROI model was to estimate the frequency of purchases per unit of time – for this we adopted a rolling 12-month period. Had this been the case of a functioning loyalty programme, this information could have easily been obtained from a database storing records of people who identify themselves with a loyalty card. In the case of a retail chain that was just about to implement a programme, this information was not available. In order to obtain it, months before implementation, surveys were conducted at points of sale. During these activities, we asked customers how many times they shopped with the chain per month, quarter and year. This information, declarative in nature, definitely introduced an element of estimation error into the model assumptions. As a result of the analyses, the scope of which cannot be grasped in this short entry, this error was determined to be 4%. This meant that the data we obtained was treated with a 96% level of confidence, estimating that the final results may oscillate around 96%-104% of the actual values.

Expectations of the loyalty programme

In creating the programme, we assumed that at a macro level we wanted it to generate three types of effects:

- Firstly, to increase the value of the shopping basket.

- Secondly, to increase the frequency of purchases.

- Ultimately, to acquire new customers who had not shopped at the retailer under review in the past 12 months.

These objectives were reflected in the ROI model. They also became the main variables of the programme. To translate these objectives into practice, three gamification levels were designed into the loyalty programme, each offering a different incentivisation factor. The higher the gamification level, the higher the benefit for the participant. This benefit was quantified by a percentage of the shopping cart value that was reinvested in the relationship with the participant. To achieve a certain gamification level, the participant was required to make purchases worth a certain amount. The higher the level, the higher the purchase threshold to reach it. The shopping threshold value that entitled a participant to take part reflected the first objective of the programme described above: to increase the value of the shopping basket. In this way, the objectives were translated into an attractive model for participants. Each person who joined the programme understood the principle that the more they buy (on other words: the more money they spend when identifying themselves during the transaction with the loyalty card embedded in the loyalty programme’s mobile application), the higher their gains. From the organiser’s perspective, it was understandable that we were grading customer reinvestment, increasing the incentive factor with the participant’s level

The modelling process itself, or in other words the parameterisation of the model, involved assuming what the percentage distribution of participants at each of the programme’s gamification levels would be, as a function of shopping basket value. In simple terms, the team that worked on the model assumed what percentage of the participants making purchases would be at a given shopping basket value level. This process attempted to determine what percentage of participants making purchases at the level of, for example, US$1,000 prior to the implementation of the loyalty programme would make purchases at US$1,200, US$1,500 and US$2,000 and above. These values are illustrative and intentionally exaggerated to allow for a better understanding of the model parameterisation process. The purchase values required for a participant to be assigned a given gamification level were captured over a 36-month period on a rolling basis (at month 37, the value of purchases made during month 1 were subtracted, at month 38, the value of purchases made during the months 1 and 2 were subtracted, and so on).

Output data

With this approach, we obtained the first relevant output of the model. By multiplying the number of customers by the average value of the shopping threshold range for each gamification level, we obtained an estimated value of the retail chain’s turnover after loyalty programme implementation. Another figure obtained was the value of incremental sales obtained solely as a result of achieving the programme’s first implementation objective, i.e. increasing the shopping basket value.

To fully describe the details of the process, three aspects need to be discussed. Aspect one – for the highest gamification threshold, we took its lower level of purchase value and multiplied by the number of customers to calculate the expected revenue. This is because the upper level was not specified. The range of the highest gamification threshold was set as USD 2,000+ (sample data), without specifying whether the threshold reaches USD 3,000 or USD 10,000. Aspect two – we assumed that 100% of the customers who were buying at the lowest shopping basket value range prior to programme implementation would continue to shop at the same level, even if they joined the programme. In other words – investing in the mass of customers generating the lowest purchase values was of no interest for us; we rather wanted to activate those who had the highest purchasing potential.

This assumption was a good reflection of the Pareto principle at the incremental sales level. In fact, 80% of the additional sales generated by the implementation of the loyalty programme were generated by the top 20% customers. Aspect three – we assumed that the potential shopping basket value increase is limited for each customer, who can only move up by one level. To illustrate this, if prior to the programme implementation, a participant was shopping at a level of USD 100-200, the peak of their potential would be an increase to the threshold of USD 250-300 (and not USD 2000+).

The above analysis describes how the first objective of the programme, i.e. shopping basket value increase, was parameterised. As you might recall, there were actually three objectives The second objective was to increase the frequency of purchases, while the third objective was to achieve an increase in the number of retail chain customers. This data was incorporated into the model using multipliers for each of matrix field where the turnover value vs. the value of gamification thresholds was distributed. In this way, we obtained two further outputs, i.e. the impact of the purchase frequency growth parameter and the impact of the number of new customers, acquired through the programme, on the value of incremental sales.

As margin value was one of the inputs, we also knew the estimated level of incremental margin that would be achieved as a result of implementing the programme.

In practice, the process of parameterising the model was significantly more complicated than what is described above. This is because estimating the number of customers who would reach a given gamification level was carried out separately for the individual product lines, each characterised by its own margins.

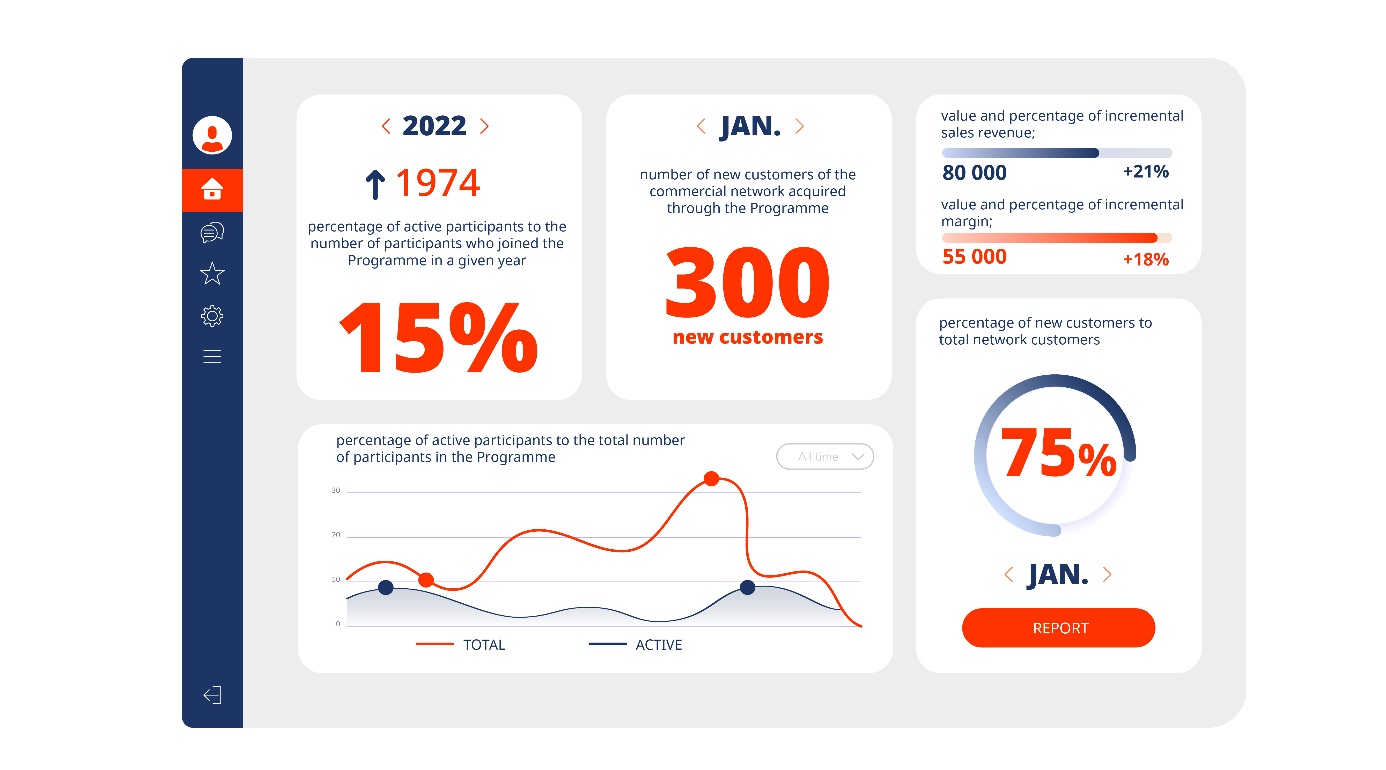

Fig. 2 Dashboard of selected ROI model ratios (sample data).

Factors. When preparing for a meeting with the Board of the retailer implementing a loyalty programme, working group responsible for preparing the model knew that explaining the model structure would be too complicated and time-consuming. We also knew that the board members would be interested in the results of the model at the level of specific parameters. After all, we guaranteed that the model structure itself would be correct and our names were signed under this declaration. We were not wrong. Therefore, we prepared selected result indicators in a model dashboard, including:

a/ percentage of active participants against the total number of participants in the programme;

b/ percentage of active participants against the number of participants who joined the programme in a given year;

c/ number of new customers of the retail chain acquired through the programme;

d/ percentage of new customers against total chain customers;

e/ value and percentage of incremental sales revenues;

f/ value and percentage of incremental margin;

g/ a number of others.

Subscriptions. The loyalty programme case study discussed here also included a subscription model. In return for payment, the participant had the opportunity to move to a higher level of gamification, even if their purchase value level did not allow this. This solution was dedicated to true fans of the brand, whose limited household budgets prevented them from making purchases of a sufficiently high value. The revenue impact of the subscription model as included above under ‘a number of others’, while also increasing the incremental value of the programme’s revenues and margin.

Cost impact. As mentioned above, the loyalty programme in question adopted the principle of progressive incentivisation rates. That is, as the value of purchases increased, participants progressed to higher gamification levels, at which they received higher benefits. This was because as the gamification level increased, so did the incentivisation factor (or, to put it simply, a higher percentage of the value of purchases made by the participant was reinvested). However, as we know well, in most loyalty programmes the take-up rate of the rewards offered is far below 100%. Whether we are talking about burning loyalty points or loyalty miles, or using vouchers – in most cases the redemption rate for rewards is less than 100%.

In a word, part of the budget previously set aside for benefits resulting from the participants’ vested rights remains unused. This is in turn reflected in the liquidation of the organiser’s balance sheet provisions. In the present case, for the purposes of the model we have assumed that this percentage will be degressive, i.e. the higher the value of the purchasing basket, the lower the offered benefits utilisation level. Why? This assumption might seem incorrect at first glance, however in our experience at i360, as society becomes more affluent, and consequently the level of spending increases, benefits offered in loyalty programmes are redeemed less often. This is because they represent a small value compared to the participants’ assets or even the value of their shopping budget. At the same time, the lower the level of spending caused by limited income, the higher the propensity of participants to take advantage of the benefits offered to them, ergo a higher take-up rate of discount coupons, burning of points or loyalty miles, etc.

Awareness of the above enabled us to prepare a two-level presentation of the data in value terms. The first level included the maximum funding requirement, the second the actual value of the budget to be spent over the next 12 months. The balance between these two parameters is precisely the value of the benefits granted and not claimed in the loyalty programme. The funds thus set aside were then spent on the various categories of expenditures that are usually incurred in connection with implementing and operating a loyalty programme, ranging from the costs of setting up an IT system and mobile app, right up to a Google Ads budget.

A dynamic view of the model. So far, I have described the ROI model in static terms. Up to here, the entire article is, so to speak, a static snapshot of a certain slice of reality. However, loyalty programmes are planned for years to come. Consequently, ROI models should also reflect the dynamics of costs, revenues and margins. In order to include these parameters in the model, it is necessary to return to the model assumptions and add parameters to make the model more dynamic, for example:

a/ percentage of customers joining the programme in the first year

b/ percentage of customers joining the programme in subsequent years

c/ churn after the first year at each of the gamification thresholds

d/ churn in subsequent years at each of the gamification thresholds

e/ number of planned points of sale openings and closings

f/ inflation rate (as a determinant for margin erosion)

g/ and many others

Assuming such parameters for the model, what remains is to extrapolate the results over the subsequent 12-month periods of the programme. This means to present a snapshot in each of the subsequent years and a final summary. In our case, this summary was precisely what the Board looked at in depth and no one “delved” into the estimates for each year. Our presentation included the following information, which was necessary for the top management:

a/ simulation of the number of participants over time

b/ current level of revenues generated by customers, broken down by shopping basket value range

c/ estimation of the revenue realised by the participants of the loyalty programme in each year adopted for the analysis (as a value and percentage)

d/ estimation dynamics of the revenue earned by loyalty programme participants over time

d/ estimate of sales growth in value and percentage terms

e/ margin value generated by participants in the loyalty programme in each of the 12 monthly periods adopted for the analysis

f/ estimation dynamics of the margin generated by loyalty programme participants in each of the 12 monthly periods adopted for the analysis

g/ cost structure of the programme (value of prizes, communication, service, etc.)

h/ incremental revenues achieved through the loyalty programme

i/ incremental margin earned through the loyalty programme

j/ result per programme in each of the 12 monthly periods

k/ fiscal year impact on P&L

l/ cash requirements to implement and execute the programme on a fiscal year basis and each of the 12 monthly periods adopted for the analysis

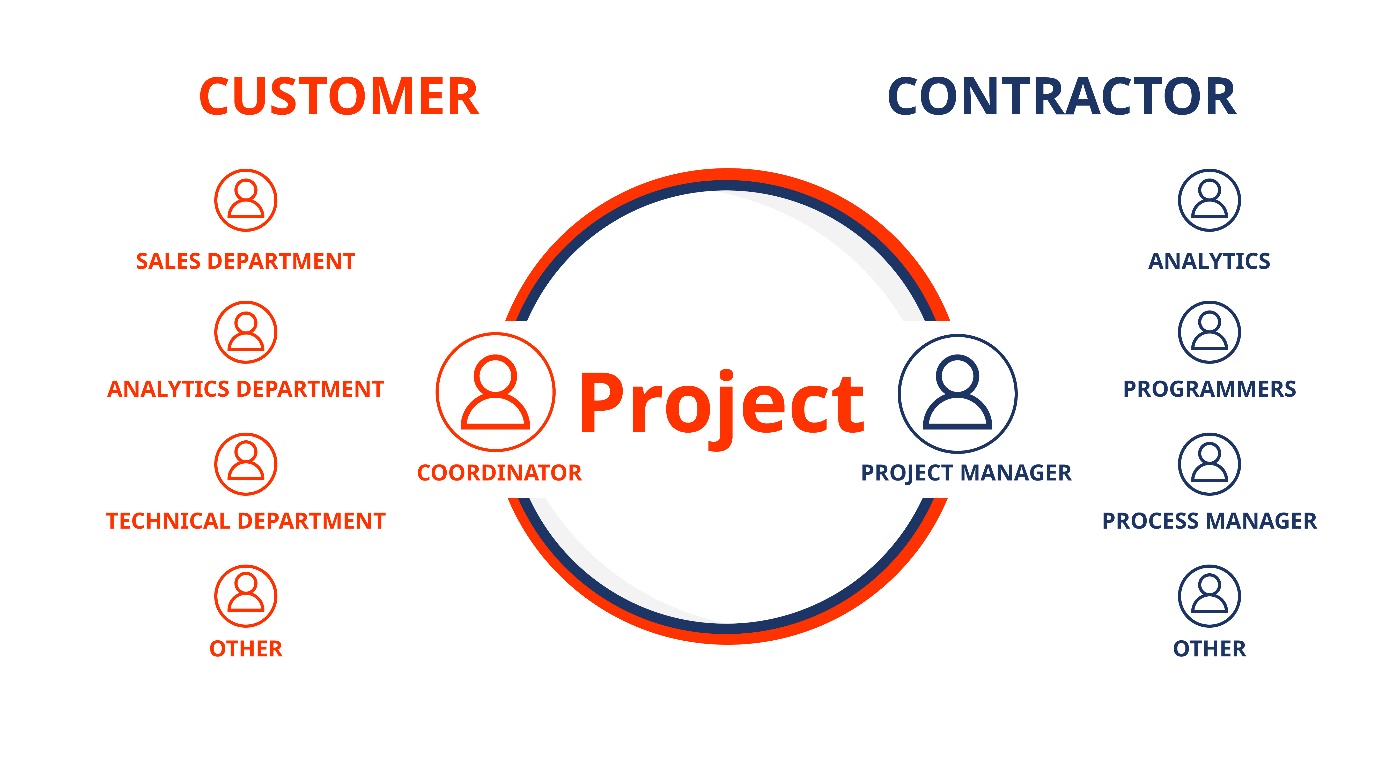

Fig. 3 Structure of the working team working on the ROI model

ROI model development process. Like any integrated system, the process of creating an ROI model also requires a project-based approach. As part of this, the most important (and at the same time the most difficult) element is to attract the right amount of attention and interest from all the necessary stakeholders. In the case in question, the demand for the creation of an ROI model was expressed at Board level, which appointed a Sales Director to lead the process. This empowerment had a very positive effect on the high level of attentiveness and responsiveness of all those requested to provide information or data.

In terms of the working group itself, success was dictated by the clear division of roles and the responsibilities assigned to them, involvement of both analysts and process architects. The framework in our case was taken from the CLMP training offered by The Loyalty Academy. All those interested in sharing your experiences are welcome to discuss them in the comments under the text or contact us personally at tomasz.makaruk@i360.com.pl.

0